From Idea to Delivery: How Discovery Supercharges Estimation Accuracy

Part 2 of the Estimation, Measurement & Forecasting Series

Teams rarely fail because they estimate poorly. They fail because they estimate too early — long before they have the clarity required to size anything with confidence.

Discovery (or ideation, in our context) is what fills that gap.

It’s how we reduce uncertainty, expose risk, and transform a vague idea into something a team can meaningfully understand.

In my current role as Agile Delivery Lead at Scilife, I work in a setup inspired by Shape Up, where discovery is explicit, timeboxed, and collaborative. The examples below draw from that experience.

Throughout this article, when I talk about uncertainty, I mean the unanswered questions, assumptions, and risks that haven’t yet been surfaced.

Why uncertainty, not estimation, is the real problem

When teams are asked to estimate too early, a few predictable patterns show up. They ask for more information — usually in the form of specs, requirements, or fully written user stories. They rarely ask many questions. Instead, they tend to take what’s presented at face value.

In some teams, estimation quietly becomes delegated. People wait for the most talkative or confident voice to lead. In teams with dedicated Engineering Managers, the team often doesn’t estimate at all — the EM does it on their behalf.

None of this is irrational. It’s what happens when teams are put under pressure to produce certainty before they’ve had a chance to build understanding.

At this point, the work is still full of unknowns, even if they aren’t named. There’s room for scope discussion, but it rarely happens. Technical dependencies are half-known or assumed away. The gap between how the system works today and what this request might change is fuzzy. What could break is largely unexplored. Testing and validation are almost never part of the conversation.

Most importantly, teams rarely pause to ask: what problem are we actually trying to solve? Instead, they accept the solution as given — and estimate that.

What follows looks like estimation, but isn’t. It’s a stand-in for missing learning.

The cost of pretending certainty exists is high. Rework becomes inevitable. Scope quietly expands. Planning turns into theatre — and over time, trust erodes on all sides.

Estimation breaks down not because teams are bad at estimating, but because they’re being asked to size work they don’t yet understand — and don’t yet know what could go wrong.

That’s not an estimation problem.

It’s an uncertainty problem.

How discovery changes the conversation

The shift is noticeable the moment the team hears:

“This week is for ideation (discovery) — not estimation.”

The energy in the room changes. Instead of working backwards from a number, the focus moves to learning. Daily conversations revolve around questions like: What did we manage to clear up yesterday? What new questions came up? What do we need to answer today? It becomes explicitly safe to say, “I don’t know yet.”

The nature of the daily syncs changes as well. They’re no longer status updates or progress reports. They become a way to orient the team around what has shifted: what’s clearer, what’s still unresolved, and where attention needs to go next.

Just as importantly, the quality of interaction between product, engineering, and QA deepens. The work stops feeling like a handover between functions and starts to feel like a shared exploration.

To protect that space, there are a few things we actively steer the team away from during discovery week. We don’t work from Jira. We avoid doing “real” implementation, except where a proof of concept helps answer a specific question.

And as the focus shifts, so do the questions teams ask.

Instead of “How big is this?” or “Can we fit it in?”, we hear questions like:

How is this actually supposed to work — and what about edge cases?

How many customers are really experiencing this problem?

This feels big — where is the meaningful starting point?

Who else in the organisation can help us understand this better?

These questions aren’t tidy. They don’t resolve neatly into numbers. But they are exactly the questions that reduce risk.

In estimation mode, teams are trying to collapse a wide, ill-defined problem into a single numerical answer. In discovery mode, teams are trying to understand what they don’t yet know — and de-risk the work as much as possible before it ever reaches delivery.

That shift is the point of discovery.

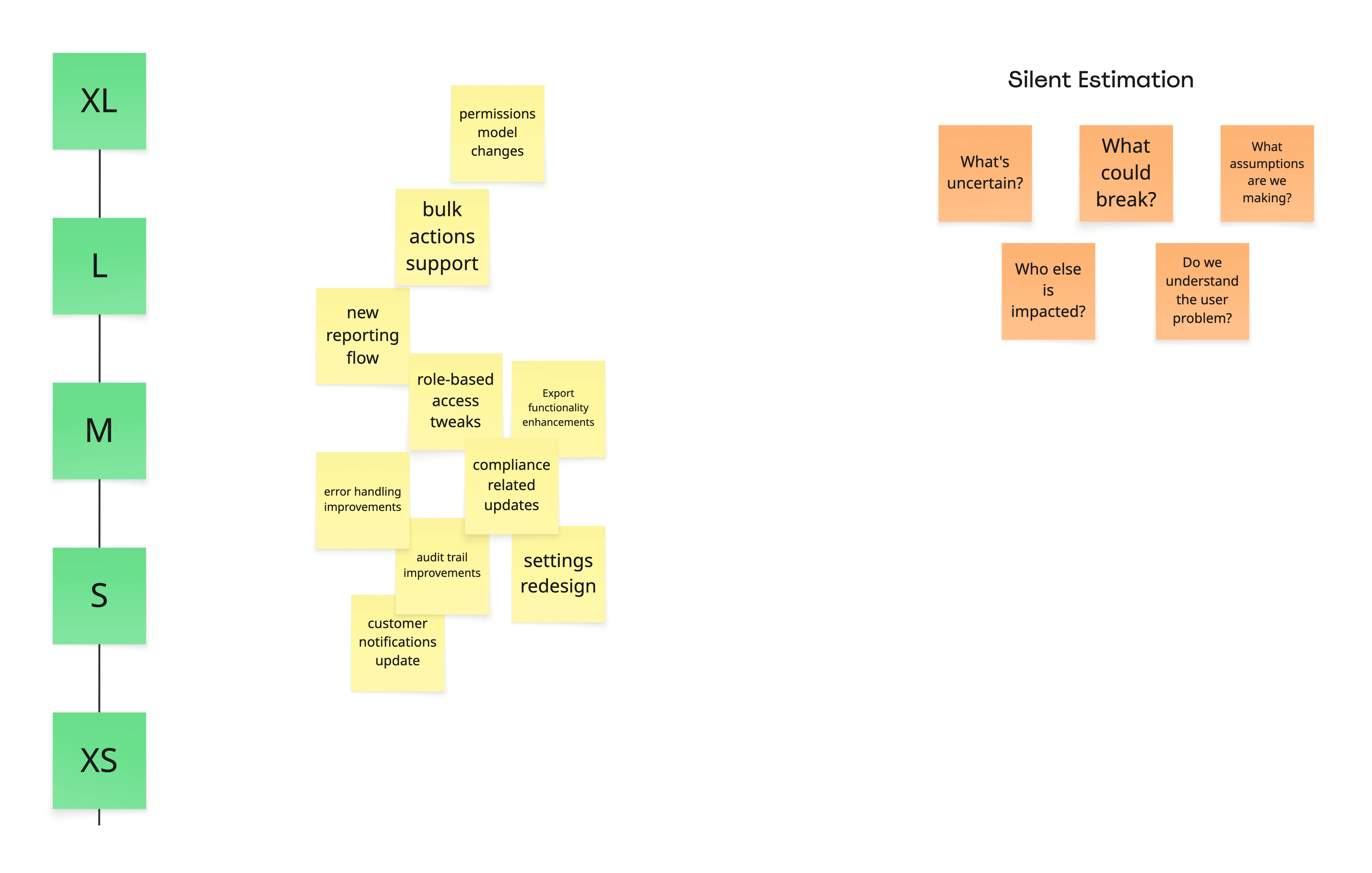

Making discovery concrete: tools that support learning

Even when teams agree that discovery matters, they often struggle with how to actually do it.

Not because they don’t care — but because they don’t know where to start. People wait for someone to facilitate. Engineers feel too far removed from users to meaningfully contribute. There’s uncertainty about how much discovery is “enough,” paired with an impatience to just start building.

This is where practical tools help. Not as a process to follow, but as scaffolding for learning.

During ideation(discovery) week, we deliberately work away from Jira and towards shared documents — primarily in Confluence. Not because Jira is the wrong tool, but because it’s the wrong tool at this stage. What we need during discovery is a place to hold evolving thinking: the topics we’re exploring, the outcomes of conversations, early technical design ideas, and the first attempts at structuring the work — without the overhead of filling in tickets before the understanding is there.

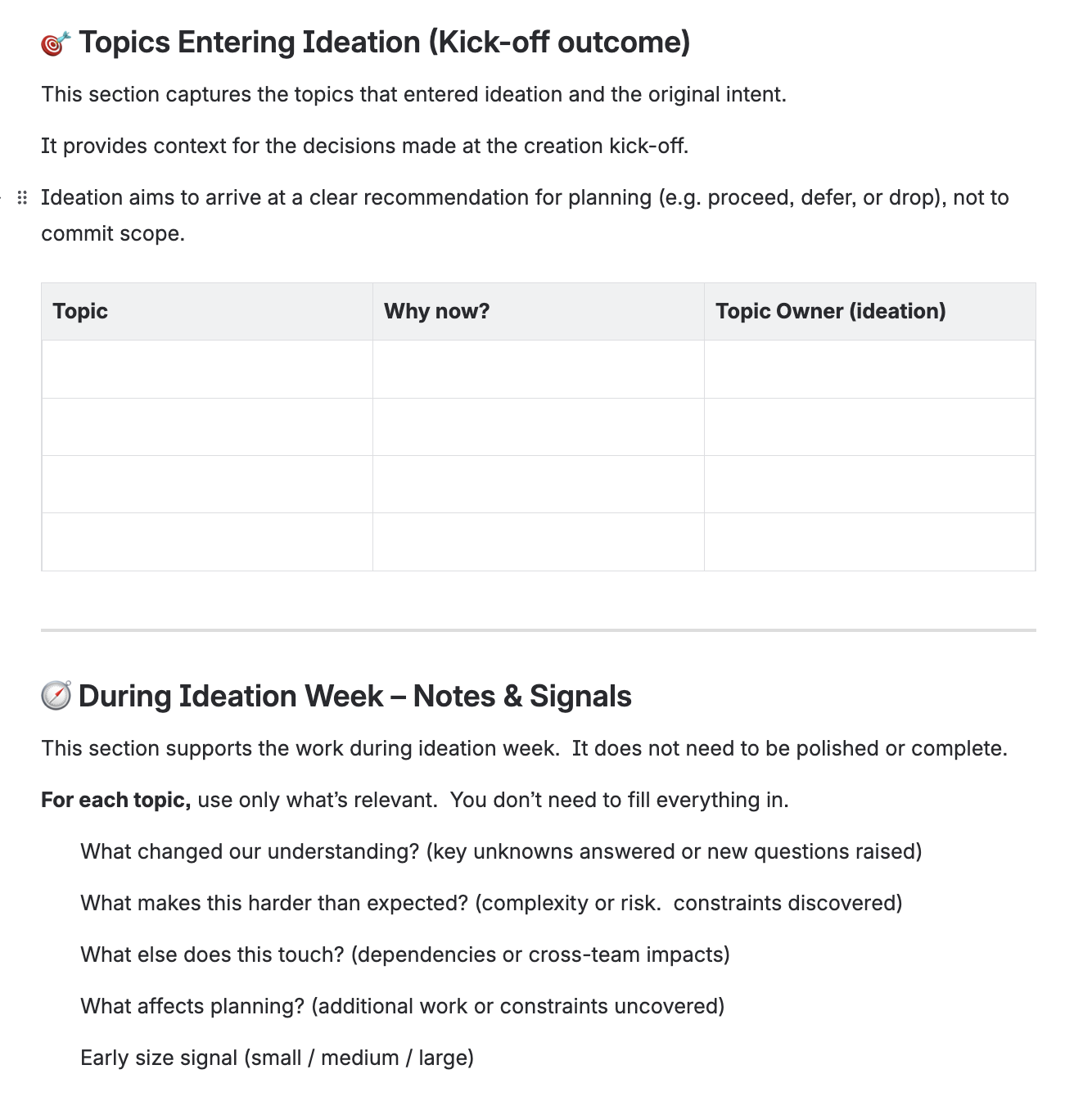

User stories that meet our Definition of Ready are usually the desired outcome of discovery week, so the team is prepared for creation. But that’s the end point, not the starting point. Often we begin with something much looser — an epic, a card from Jira Product Discovery, or even just a loosely framed topic — simply to get the conversation going.

To support that way of working, we use a simple ideation template. Its purpose isn’t to standardise thinking or force completeness. It’s to help the team keep track of what’s being explored, why it matters now, and who is driving each topic. At its core, the template is just a lightweight table, with space underneath for thinking to evolve.

The prompts are intentionally minimal. Teams use only what’s relevant:

- What changed our understanding?

- What makes this harder than expected?

- What else does this touch?

- What affects planning?

- An early size signal (small / medium / large)

The template stays stable over the week, but the content underneath it grows. In many cases, those sections expand into standalone Confluence pages, Miro boards, or technical notes as the thinking deepens. The template doesn’t try to contain discovery — it simply keeps learning visible and traceable.

Alongside these artifacts, teams rely on a small set of discovery methods to create momentum. Journey mapping helps shift the conversation away from solutions and toward the user’s experience. Prototyping makes ideas tangible early, without committing to them. Event storming surfaces hidden complexity and aligns understanding across roles.

What matters more than the tools themselves is what they enable: surfacing questions that were previously implicit. They invite different perspectives into the conversation and make assumptions visible. In the best cases, they help teams build empathy for the user — not as an abstract persona, but as someone whose experience the team can reason about together.

By the end of a good discovery week, a few things are usually true. We have user stories that meet our Definition of Ready. We have early technical designs or proof-of-concepts where they were needed. There’s often agreement on a phased approach if the work turned out to be larger than expected. And we have a clearer picture of dependencies and outstanding questions.

These are the kinds of tools and practices we work with in our Product Discovery & Design Thinking workshop — not as a fixed toolkit, but as a way to help teams navigate uncertainty with more confidence before delivery begins.

Why discovery improves estimation — without estimating

By the time discovery is done well, something important has already changed.

The team hasn’t produced a number.

But they’ve reduced uncertainty.

They’ve surfaced assumptions and risks early, rather than discovering them mid-delivery. They’ve explored the edges of the work: what’s in scope, what’s out, what’s dependent on other teams or systems, and where the real complexity lies.

Most importantly, they’ve built a common mental model of the work.

That’s what makes estimation possible later.

When teams estimate after discovery, they’re no longer guessing at a vague request or a pre-packaged solution. They’re sizing work they’ve already interrogated, discussed, and de-risked. The conversation shifts from “What do you think?” to “Based on what we now know…”

Discovery doesn’t make estimation disappear.

It makes it meaningful.

And it changes what estimation is used for. Instead of standing in for missing learning, estimation becomes a calibration step — a way to compare work, sequence it, and prepare for delivery with far fewer surprises.

That’s the role discovery plays in this series.

It sits squarely in the Learn phase — reducing uncertainty so that everything that follows has a stronger foundation.

One thing to try this week

Before your next estimation or planning conversation, run a one-hour discovery checkpoint.

Pick one upcoming topic — not a big initiative, just something that’s about to be sized.

For one hour, explicitly suspend estimation and focus only on learning. Ask the team to answer three questions together:

- What do we understand well about this problem?

- What are we still unsure about or making assumptions about?

- What would reduce uncertainty the fastest?

(A conversation, a sketch, a prototype, a technical spike, a user check.)

Capture the answers in a shared document — not in Jira.

If, at the end of the hour, the team still feels unsure how big the work is, don’t force an estimate. Use that uncertainty as your signal: discovery needs more space.

You haven’t delayed delivery.

You’ve prevented guessing.

What’s next

In the next article, we’ll move one level down.

Part 3: Getting Granular — Estimating User Stories Like a Pro looks at what happens once discovery has done its job. We’ll explore how teams estimate at the story level, how shared understanding shows up in sizing conversations, and how teams develop a consistent internal sense of what their estimates actually mean — without turning estimation into overhead or theatre.

Discovery sets the conditions.

Story-level estimation is where those conditions get tested before measurement and forecasting enter the picture.

💭 Before you go

What would change if your team treated estimation as a follow-up to learning — rather than a substitute for it?

👉 Try this:

Before your next estimation session, pause and ask:

“What do we still not understand well enough to size this confidently?”

If the list is long, that’s not a failure — it’s a signal that discovery still has work to do.